Category: Cat Health

Great Pet Care - Pet health information — simplified.

Cat X-Ray: Cost and What to Expect

- 2025-03-04T01:43:01

- Sarah J. Wooten, DVM

Veterinarians use X-rays and other types of medical imaging to see structures inside the body so they can diagnose and treat their patients. If you have a cat, then there is a good chance that they may need to be X-rayed at some point in their lifetime.

So what happens during a cat X-ray, is it risky, and how much does it cost? In this article, we will cover everything you need to know about cat X-rays so you’ll feel more prepared if your pet ever needs one.

What Is an X-Ray?

X-ray technology is used within the medical specialty called radiology. Radiology uses different types of medical imaging, including X-rays, to diagnose diseases and guide treatment choices. A radiologist is a doctor who receives additional training to read X-rays and other types of imaging studies, such as MRI and ultrasound.

X-rays are a form of electromagnetic radiation with extremely short, high frequency wavelengths. The ability of X-rays to penetrate objects that do not allow light to pass through them (“optically opaque”), such as the body, led to their application in medicine. X-rays are used with photographic plates to create pictures called radiographs. Calling the pictures made with X-rays an “X-ray” is actually a misnomer. Although the correct term is “radiograph,” to avoid confusion, we will continue using the term “X-ray” in this article.

X-ray pictures used to be created on photographic film. Nowadays, most X-rays are digital, which is a more convenient and economical way of storing X-ray images. Digital X-rays are easily shared, so if your cat needs to see a specialist, your veterinarian can just email the digital copies. Because digital copies are so easy to share, many veterinarians now use radiology services to read their X-rays. Your vet can also easily share the X-rays with you so you can have a record.

X-rays are very useful in seeing certain conditions in the body, but not all conditions. X-rays work best for imaging bones, joints, large body cavities, large organs, and structures that don’t allow X-rays to pass through them (“radio-opaque”), such as swallowed or inhaled foreign bodies and some bladder stones.

The soft tissues of the body don’t absorb X-rays well, which can make it more difficult to evaluate soft tissues and small organs with pictures taken by X-ray. In these cases, a special imaging procedure called contrast radiography can be used to provide more detailed images. With contrast radiography, a harmless dye is given by various routes that blocks X-rays, and then a series of X-ray pictures are taken.

Cat Ultrasound vs. X-ray

While X-rays can give veterinarians a lot of information, sometimes additional information is needed. In these cases, X-ray is often combined with other imaging types, such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, to give the doctor a more complete picture. Ultrasound, for example, uses sound waves to make moving pictures, and is very good for imaging soft tissue structures in the abdomen and chest. By combining different imaging studies, your veterinarian can use more complete information to diagnose and treat your cat.

Why Do Cats Need X-Rays?

A veterinarian will order cat X-rays for a variety of reasons. X-rays are often included in preliminary diagnostic testing for many conditions and symptoms, including:

- Cancer

- Limping

- Trauma or other injuries

- Vomiting

- Abdominal enlargement

- Coughing

- Dental disease

- Heart disease

- Swallowing abnormalities

- Difficulty breathing

- Urinary tract symptoms, including bloody urine, increased urination, and straining to urinate

- Intervertebral disc disease

X-rays are most useful for detecting:

- Fractures

- Injuries

- Deformities

- Osteoarthritis

- Tumors

- Obstructions

- Dental disease

- Enlargement or deformity of medium to large internal organs, such as the stomach, liver, heart, and kidneys

- Fluid

- Air

In these situations, X-rays can confirm a diagnosis, locate a problem, and provide information on how the condition should be treated. X-rays can also be used to track progress during treatment, such as rechecking a bone after a fracture has been repaired surgically.

Types of Cat X-Rays

While any part of the body can be X-rayed, it is more beneficial to focus X-ray diagnostics on locations where vets can obtain a clear picture. The most common X-rays performed in cats include the following:

Chest X-rays to view structures in the thoracic cavity including heart, lungs, large vessels, diaphragm, esophagus, windpipe, and pulmonary cavity. Chest X-rays also provide information on the ribs, thoracic spine, and body wall of the chest.

Abdominal X-rays are used to view structures in the abdomen, including stomach, intestines, liver, kidneys, bladder, ureters, and spleen. Abdominal X-rays also provide information on the lumbar and sacral spine, as well as the pelvis and hip joints.

Other common X-ray studies in cats include:

- Bones and joint X-rays to assess injuries, swellings, or signs of lameness

- Dental X-rays

- Skull X-rays

- Cervical (neck) X-rays

Veterinarians must use a different, smaller X-ray machine to take dental X-rays that provide up close, detailed pictures of the teeth and jaw bones.

What to Expect During a Cat X-Ray

Most X-rays can be done on an outpatient basis, sometimes even while you wait in the exam room. As long as the cat stays still for the procedure, it is very quick. Veterinary technicians will cover themselves with lead aprons to block X-rays and restrain your cat on an X-ray table to take the picture. Pet parents are generally not allowed to be with their cat during an X-ray because of OSHA regulations. The X-ray technician will narrow (“collimate”) the X-ray beam down to the smallest size to avoid unnecessary exposure to X-rays.

While X-rays are not painful, some cats become frightened by the sights and sounds of the equipment and restraint. To help these cats have a better experience and allow the technician to take good X-rays, veterinarians often recommend sedating the cat so they feel sleepy and relaxed.

In some cases, your vet may be able to diagnose the problem right away with an X-ray. In other cases, they will need to send the film to a radiologist for interpretation, which can take up to 24 hours.

Cat X-Ray Cost

The cost of cat X-rays depends on several factors, including:

- The cost of living in your area

- How many X-rays your cat needs

- Whether your cat has to be sedated for X-rays

- Any additional special X-ray studies, such as contrast dye studies

The following is a cost guide, but always check with your veterinarian:

- Dental X-rays: $50-$150

- Chest or abdominal X-rays: $100-$200

- Bone or joint 2 view X-rays: $75-$150

- Whole body X-rays: $250-$350

- Spinal X-rays: $200-$1,000 depending on whether cat requires sedation

If your cat requires sedation or special X-ray studies, like contrast dye studies or fluoroscopy (which is X-rays in motion), the cost will go up.

Pet parents have several options that they can use to offset the cost of veterinary care, such as pet insurance, line of credit, emergency credit card, or wellness plans offered through the veterinary clinic.

Hypercalcemia in Cats

- 2025-01-31T20:19:07

- Catherine Barnette, DVM

Veterinarians run blood tests on cats for a wide variety of reasons. Sometimes, blood tests are intended to diagnose the cause of a cat’s illness. Other times, bloodwork is run for screening purposes, as part of an annual wellness exam or in preparation for anesthesia.

Hypercalcemia is one of many conditions that can be diagnosed based on a cat’s bloodwork. Some cases of hypercalcemia are mild, requiring minimal interventions and carrying a relatively good prognosis. Other cases are far more significant. Read on to learn more about hypercalcemia in cats.

What Is Hypercalcemia in Cats?

Hypercalcemia is defined as abnormally high levels of calcium in the blood.

Under normal circumstances, your cat has systems in place that regulate blood calcium. Parathyroid hormone, calcitriol (the active form of vitamin D), and calcitonin (a hormone released by the thyroid gland) all play a role in regulating blood calcium.

Hypercalcemia can be caused by a wide variety of conditions, which can affect any of these calcium regulatory systems. Hypercalcemia is most common in older cats, but it can affect cats of any age.

Hypercalcemia vs Hypocalcemia

Hypercalcemia refers to increased blood calcium. “Hyper” is a prefix that means excessive, and “-calcemia” is a root wood that refers to blood calcium. Therefore, a cat with hypercalcemia has excessive calcium in the blood.

You may also hear veterinarians refer to hypocalcemia. “Hypo” means low or below normal. Therefore, a cat with hypocalcemia has abnormally low levels of calcium in the blood.

It’s easy to confuse these words, especially if your veterinarian is speaking quickly. If you’re unsure which condition your veterinarian is describing, ask for clarification.

Causes of Hypercalcemia in Cats

Hypercalcemia in cats can have many potential causes. However, the three most common causes are:

- Kidney disease: The kidneys play an important role in regulating the levels of calcium and other substances in the blood. When the kidneys aren’t working correctly, calcium can build up to abnormally high levels.

- Malignant cancer: Some cancers, including lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma, have been shown to cause hypercalcemia in cats.

- Idiopathic hypercalcemia in cats: This is one of the most common causes of hypercalcemia in cats. “Idiopathic” means hypercalcemia arises spontaneously, with no known cause. These cats do not have any underlying diseases that can be found as a cause of their hypercalcemia, despite extensive testing.

Less common causes of hypercalcemia in cats include:

- Adrenal hormone insufficiency

- Destructive bone disease (infection, bone cancer)

- Fungal infection

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Nutritional imbalances

- Vitamin D toxicity (caused by rat poison)

Genetics doesn’t seem to play a role in hypercalcemia. No specific breeds have been found to be at higher or lower risk of hypercalcemia.

Hypercalcemia in Cats Symptoms

Clinical signs of hypercalcemia can vary widely. Some cats are completely asymptomatic, while others are very sick by the time their condition is diagnosed.

Signs of hypercalcemia in cats may include:

- Decreased appetite

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Lethargy

- Weakness

- Dehydration

- Increased thirst

- Increased urination

- Abdominal pain

- Muscle spasms

- Seizures

It’s important to note that the signs of hypercalcemia mimic the signs of many other conditions. This condition can’t be diagnosed on clinical signs alone.

Diagnosing Hypercalcemia in Cats

Hypercalcemia is diagnosed based on a blood test. If your cat is showing vague signs of illness, your veterinarian will likely recommend blood tests to evaluate your cat’s health. In a cat with hypercalcemia, blood tests will show an abnormally high blood calcium level.

Not all elevated calcium levels are clinically significant. Calcium levels can fluctuate over time, and they may be briefly elevated but then return to normal. If your cat’s blood calcium is elevated on screening bloodwork, your veterinarian will probably perform further testing to be sure the elevated calcium level is significant. This may involve rechecking blood tests a few days later or sending your cat’s blood to a reference laboratory, which can perform more specialized tests. If your cat’s blood calcium elevation is found to be significant, your veterinarian will diagnose your cat with hypercalcemia.

After receiving a hypercalcemia diagnosis, the next step is figuring out the underlying cause. Your veterinarian will recommend further tests to look for potential causes of hypercalcemia. Further testing may include additional blood tests, urinalysis (to check kidney function), imaging (to look for cancer), and other diagnostics. It’s important to determine the cause of your cat’s hypercalcemia (if possible), because this determines the best treatment for your cat.

Hypercalcemia in Cats Treatment

If your cat is very sick with hypercalcemia, your veterinarian will take steps to lower your cat’s blood calcium levels quickly. This may include intravenous (IV) fluids, diuretics (to encourage calcium elimination in the urine), and other medications.

Next, your veterinarian will shift to long-term treatment strategies.

If possible, your veterinarian will aim to control the underlying cause of your cat’s hypercalcemia. This is the best treatment for hypercalcemia. Treatment may involve fluid therapy and dietary changes for kidney disease, chemotherapy or surgery for cancer, or other treatments.

If the underlying cause of your cat’s hypercalcemia cannot be determined and/or treated, your veterinarian will start your cat on long-term medications. These medications are intended to reduce your cat’s blood calcium levels. The efficacy of these medications can vary, and these medications may cause significant side effects. Therefore, it’s always best to control the underlying cause of hypercalcemia, if possible.

What to Feed a Cat with Hypercalcemia

Your veterinarian will recommend the best diet for your cat. There is no single best cat food for hypercalcemia.

If your cat’s hypercalcemia is caused by an underlying disease, your veterinarian will probably recommend a diet to help manage the underlying disease.

If your cat has idiopathic hyperthyroidism, your veterinarians may recommend a diet that is low in calcium. Diets that are low in carbohydrates, high in protein, and/or high in fiber have also been recommended to reduce hypercalcemia, although research in this area is limited and opinions vary.

Cost to Treat Hypercalcemia in Cats

The cost to treat hypercalcemia will vary, depending on the underlying cause of your cat’s condition.

The initial diagnostic testing for hypercalcemia can cost anywhere from a few hundred dollars to over $1,000, depending on your cat’s individual case.

If your cat has mild hypercalcemia that can be addressed through a dietary change, the cost of treatment and monitoring may be as low as several hundred dollars per year. If your cat has lymphoma or another malignant cancer, treatment may cost several thousand dollars.

Your veterinarian can provide a more educated estimate of treatment costs once they have determined the underlying cause of your cat’s hypercalcemia.

How to Prevent Hypercalcemia in Cats

Given the wide variety of conditions that may cause hypercalcemia, there is no way to definitively prevent this condition. However, there are steps you can take to reduce your cat’s risk, such as:

- Feed a well-balanced diet. An imbalanced diet is one potential cause of hypercalcemia.

- Keep your cat away from toxins and human nutritional supplements, both of which may impact blood calcium levels.

- Follow your veterinarian’s recommendations for wellness exams and bloodwork monitoring. Most veterinarians recommend annual bloodwork for cats. Screening bloodwork can aid in the early diagnosis of hypercalcemia, in addition to many other diseases.

- Seek veterinary care if you notice weight loss, lethargy, or other signs of illness.

While there’s no way to definitively prevent hypercalcemia, paying attention to your cat’s health and following your veterinarian’s recommendations can help reduce the risk.

Cat Spay and Neuter: Cost, Procedure and What to Expect

- 2025-01-30T01:24:54

- Kathryn Heigel-Meyer, DVM

If you ever watched “The Price is Right” when Bob Barker hosted, you might remember his famous sign-off reminding viewers to “have your pet spayed or neutered.” As an animal lover, Barker saw how the pet overpopulation crisis was causing mass euthanasia of stray animals in shelters.

In the 1970s, tens of millions of animals each year were being euthanized [1]. With the help of many animal advocates like Barker and Betty White, we have been able to get the euthanasia rate in animal shelters down to less than 1 million euthanasias each year, per the ASPCA [2]. Better yet, 4.1 million animals are adopted out each year! These numbers have improved mostly from the advocacy and promotion of spay and neuter programs to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

So now that you know why so many people are passionate about this simple procedure, let’s talk about what actually goes on during a cat spay and neuter appointment. We’ll also cover benefits, costs, and how to care for your kitty after surgery.

Understanding Cat Spay and Neuter Procedures

We’ll begin by explaining the difference between a cat spay and a cat neuter procedure:

Cat spay. A “spay” is the simple term for an ovariohysterectomy. In this procedure, the veterinary surgeon removes a female cat’s ovaries and uterus. By removing all the structures involved with reproduction, there is no chance of pregnancy.

Cat neuter. For male cats, veterinarians perform a “neuter,” or orchiectomy. This quick procedure simply involves removing the testicles to prevent male cats from impregnating female cats.

It’s important to note that unlike a spay, where a female cat is unable to get pregnant immediately following the procedure, a male cat can remain fertile for up to six weeks following the surgery. Pet parents should be cautious if a recently neutered male cat is around any “intact” females (cats who haven’t been spayed) during that time period.

Reasons to Schedule a Cat Spay or Neuter Appointment

Besides preventing unwanted pregnancies — and the costs associated with them — there are multiple benefits to having your cat spayed or neutered. This includes:

- Reduce the risk breast cancer and uterine infections

- Reduce the urge to roam and fight other cats

- Eliminate the incessant wailing that female cats do when they are in heat

- If done early, can eliminate risk of spraying behaviors

- Reduce the risk of FIV and FeLV infections from fighting

- Decrease the number of homeless pets

- Prolong your cat’s life

At what age can you spay or neuter a cat?

You can schedule your cat to be “fixed” as early as 8 weeks of age. There is also no upper age limit for this surgery. If you have an older cat who you want to get spayed or neutered, then you can get them altered as well.

Cats can reach sexual maturity at around 4 months of age. If you are having difficulty finding a place to book a cat spay or neuter appointment and your cat is mature in age, then make sure to separate male and female cats until you can get them in for surgery.

Remember that it can take a couple of weeks to get an appointment, so make sure you schedule it as soon as possible to prevent any accidental pregnancies.

Risks to consider

Any procedure that requires anesthesia carries some risk. However, this common surgery for cats is generally considered safe. The benefits of the procedure will almost always outweigh the risk. However, if your cat has an underlying medical condition, such as heart disease or seizures, then you should discuss those risks with your veterinarian.

Are there any alternatives to surgery?

There are currently no approved non-surgical contraceptive (a drug to prevent pregnancy) treatments available for cats. However, researchers are working on medications that can provide long-term sterilization for cats without the need for surgery.

How Much Does Spay and Neuter Cost for Cats?

The cost to spay or neuter a cat typically depends on your geographic location and where you have it done. In addition, spay surgeries tend to be more expensive than neuter surgeries since the procedure is more involved.

If you have the surgery done at a private veterinary clinic, it can run you between $300-$500, and sometimes higher. However, there are low-cost alternatives to consider. Many animal shelters and humane societies offer low-cost spay and neuter surgeries that can run between $50-$150. It is important to know that just because the surgery is less expensive, it does not mean that they cut corners or do less quality work. In fact, these surgeons are extremely qualified to perform this procedure and the staff are just as caring.

Cat Spay or Neuter Appointment: What to Expect

If your cat is an adult, you will be asked to fast your pet (not let them eat) prior to the surgery. However, your veterinarian may ask you not to fast your kitten because they could become hypoglycemic (low blood sugar). Cats who are easily stressed may be given medications, such as gabapentin, to take prior to their appointment.

When you bring your cat in for a spay or neuter appointment, you can expect a safe, straightforward procedure. The surgery is done under general anesthesia, so your cat will be fully asleep and pain-free during the surgery. The entire procedure can take anywhere from 15 minutes to 1 hour. Afterward, your cat will be monitored closely to make sure that they recover comfortably.

Here is a more detailed explanation of what goes on during a cat spay vs. cat neuter surgery:

Cat Spay Appointment

During a cat spay procedure, the veterinary surgeon will make an incision in the midline of the female cat’s abdomen where there is no muscle and only ligament. By entering the abdomen at this location, the veterinarian is decreasing the bleeding and pain that could occur. Next, they remove the cat’s ovaries with an instrument called a spay hook. Then, they remove the fallopian tubes and uterus. Last, the surgeon ties off (ligates) all the vessels and tissue and closes the abdomen with sutures.

Cat Neuter Appointment

During a cat neuter procedure, the veterinary surgeon makes an incision on the scrotum and literally pops out the testicles. Then, they tie off the spermatic cord that contains structures, such as the artery, vein, muscle and vas deferens, to prevent bleeding.

Occasionally, in certain cats, one or both testicles do not descend into the scrotal sac properly. When this happens, the surgeon needs to make an abdominal incision, similar to a spay incision, and remove the cat’s testicle(s) from the abdominal cavity.

- Schedule veterinary appointments

- Fill approved prescriptions

- Stay on top of your pet's wellness needs, all in one convenient place

Cat After Spay or Neuter Surgery: Care Tips

Most cats will be able to go home the same day after their spay or neuter surgery, although they may be groggy and need extra care for a few days. This includes a quiet, comfortable space for them to relax and limit their activity.

Make sure that you follow your veterinarian’s post-operative instructions closely and give any pain medication as directed. Your cat’s appetite should return within 24 hours of coming home. If it does not, then contact your veterinarian’s office. You should also monitor the incision site for any signs of infection, such as swelling and redness.

While many cats bounce back quickly, it’s essential to restrict their activity for 7-10 days, including preventing them from jumping, running, or playing rough.

By spaying or neutering your cat, you are not only giving them a lifetime of health benefits, including a reduced risk of certain cancers and behavioral issues, but you are also helping prevent unwanted pregnancies and decreasing the number of pets in shelters.

References

- Rowan, Andrew, and Tamara Kartal. “Dog Population & Dog Sheltering Trends in the United States of America.” Animals: an open access journal from MDPI vol. 8,5 68. 28 Apr. 2018, doi:10.3390/ani8050068

- Pet Statistics. ASPCA. Retrieved from https://www.aspca.org/helping-people-pets/shelter-intake-and-surrender/pet-statistics

Whipworms in Cats

- 2024-12-30T21:36:55

- Emily Swiniarski, DVM

If you’ve ever welcomed a kitten into your home (or are about to), there’s a good chance the topic of cat worms has (or will) come up. Maybe even more often than you’d like! Veterinarians often focus on roundworms and hookworms when discussing the importance of deworming. However, lesser-known whipworms in cats deserve air time, too.

Though only about 0.1 percent of pet cats in the U.S. have whipworms [1], understanding this rare parasite is essential. Treatment for whipworms differs significantly from other cat worms, so it’s vital to know what to expect and how to protect your pet.

Here’s everything you need to know about whipworm in cats, from the symptoms your kitty may show to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention tips.

What Are Whipworms?

Whipworms are a parasite in the genus Trichuris. These tiny, thread-like nematodes live in the colon or in the large intestine. Because they are rare in cats, the impact is low for most felines. Though severe infestations can lead to health issues like anemia.

Unlike roundworms, which are more likely to cause noticeable symptoms, such as diarrhea, feline whipworm infections often go undetected. That’s why knowing what to watch out for to ensure speedy diagnosis and treatment is crucial for maintaining your cat’s health.

Because they are rare in cats, the impact is low for most cats. Roundworms and hookworms are much more prevalent and more often associated with symptoms like diarrhea.

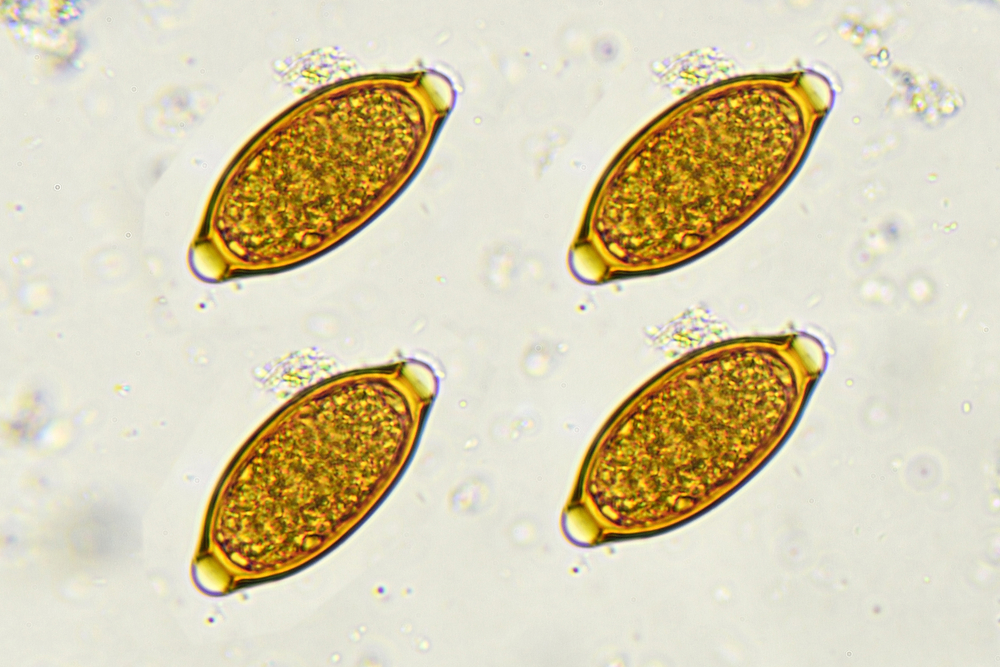

What do Whipworms Look Like?

Whipworms are slender, white to off-white worms measuring 2–3 inches long. Their bodies are mostly thin, with one end widening significantly, giving them a whip-like appearance. The thicker part resembles the handle of a whip.

While adult whipworms are visible to the naked eye, whipworm eggs in cat feces are microscopic. You won’t see these eggs without a microscope, but they play a key role in transmitting the infection.

How Do Cats Get Whipworms?

Cats develop a whipworm infection by ingesting soil, food, or water contaminated with the parasite’s eggs.

Cats cannot give the infection to one another directly. However, when an infected cat defecates, they shed whipworm eggs in their feces (poop).

It takes 9 to 21 days for these eggs to mature and become infective. These infective eggs can survive for years in harsh conditions. Once a cat ingests an infective egg, it hatches in their intestines, growing into an adult whipworm within 3 months.

Outdoor cats have an increased risk of getting a whipworm infection. Certain regions of the United States may have higher prevalence as well. A study on outdoor cats in Florida found whipworms in 38 percent of cats [2] – a marked increase from just 0.1 percent of domestic cats nationwide.

Can Humans Get Whipworms from Cats?

Whipworms are highly species-specific. Cat whipworms infect only cats, so humans are not at risk. While there are rare cases of humans contracting whipworms from dogs, there are no such reports involving cats.

Still, you never know what parasites or animals may be hanging around your yard. So it’s always best to practice good hygiene to reduce the risk of transmission. Always wash your hands thoroughly after cleaning up animal feces or working with potentially contaminated soil.

Whipworm Symptoms in Cats

In cats, whipworms survive by feeding off feline blood and the lining of the intestine. Most cats with whipworms show no apparent symptoms. However, in severe cases, the parasitic worms can cause significant blood loss.

In some cases, this can trigger anemia (low red blood cells), which can cause subtle symptoms over time. In kittens, these signs are more dramatic because they are smaller and have less blood to lose.

Symptoms may include:

- Diarrhea

- Frequent trips to the litter box to poop

- Weight loss

- Less active

- Pale gums (pale pink instead of healthy vibrant pink)

- Belly pain

If you notice any of these symptoms, consult your veterinarian for testing and treatment.

Diagnosing Whipworms in Cats

If your vet suspects your cat may have whipworms, you’ll need to bring your cat in for a visit. However, veterinarians cannot diagnose the condition with a physical exam alone.

Instead, vets rely on diagnostic tests to confirm whether or not a cat has whipworms. There are two types of tests:

- Fecal Flotation: Vets mix a cat’s feces with a sugar solution that causes parasite eggs to rise. Then they examine these eggs under a microscope to identify the parasite.

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): Since whipworms do not constantly shed eggs, this highly-sensitive test looks for antigens (tiny particles of adult whipworms) in the feces to confirm the diagnosis.

Whipworm in Cats Treatment

There are no medications specifically approved for cat whipworm infections. However, vets often prescribe antiparasitic drugs off-label as an effective treatment.

Whipworm Medication for Cats

Fenbendazole (brand name Panacur) – Whipworms have an incredibly long lifecycle. So vets often use the “3 days, 3 weeks, 3 months” approach when prescribing this deworming medication.

First, your cat takes fenbendazole for three days to kill the adult whipworms. Then again three weeks later to kill any newly matured adult. However, the medicine does not kill larvae (immature parasites). So you must treat again three months later, after those larvae become mature adults, to ensure all the worms are gone.

“Combo” or “comprehensive” flea preventives – Some monthly flea medications contain additional ingredients that target other parasites. While many of these multi-purpose meds target only roundworms and hookworms, several contain ingredients effective against whipworm, including:

- Milbemycin oxime

- Moxidectin and imidacloprid

- Emodepside and praziquantel

General Cost

The cost of diagnosing and treating whipworms typically includes:

- Veterinary exam and fecal tests: $300–$500, depending on additional treatments for symptoms like diarrhea.

- Medication: This can range from $20-$80, depending on what your vet prescribes.

How to Prevent Whipworm in Cats

The best strategies for preventing whipworms include:

- Keeping cats indoors to minimize exposure to contaminated soil or feces.

- Using monthly parasite preventives effective against whipworms.

- Cleaning litter boxes regularly and reduce the risk of environmental contamination.

By staying vigilant and mitigating risks, you can keep your cat safe from whipworms. Though the likelihood of whipworms in cats is small, the sets you take can help guard against other intestinal parasites. And that’s a win-win for you and your cat!

References

- Nagamori, Yoko et al. “Retrospective survey of parasitism identified in feces of client-owned cats in North America from 2007 through 2018.” Veterinary parasitology vol. 277 (2020): 109008. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2019.109008

- Geng, Jinming et al. “Diagnosis of feline whipworm infection using a coproantigen ELISA and the prevalence in feral cats in southern Florida.” Veterinary parasitology, regional studies and reports vol. 14 (2018): 181-186. doi:10.1016/j.vprsr.2018.11.002

Pale Gums in Cats: 8 Reasons It Might Be Happening

- 2024-12-26T16:13:06

- Alicia Ashley, DVM

When was the last time you checked your cat’s gums? If you answered, “Um, never,” don’t fret. Unless you brush your cat’s teeth, the average pet parent isn’t peeking in their cat’s mouth too often. After all, it’s not typical cat fashion to open wide and say “ahhh” upon request. (If only it were that easy…but stay tuned for tips, because it’s not hard either.)

Why does checking your cat’s gums matter? Believe it or not, the gums give clues about your cat’s hydration, circulation, oxygen levels, and the presence of certain diseases. Pale gums in cats are a sign of serious health issues requiring veterinary attention. In this article, we’ll discuss pale cat gums vs normal-looking cat gums, possible causes, and what to do if you encounter paleness in your kitty’s gums.

Cat Gum Basics: What Color Should Your Cat’s Gums Be?

Healthy cat gums should be light pink, shiny, and moist, although some color variations are normal. Some cats (especially orange kitties) develop brown or black freckles on their gums, a harmless feature called lentigo (it usually appears on their eyelid margins, lips, and nose, too). Other cats may have more generalized dark pigmentation of their gums (especially black and gray cats).

Like our own gums, cat gums consist of a specialized tissue called a mucous membrane, which lines and protects many internal areas of the body. The gums act like a mirror of health, giving clues about several conditions. Some conditions may cause your cat’s gums to become inflamed or turn blue, purple, red, or yellow. (You can learn more about these here.)

Pink gums are an indication of good oxygen levels and blood flow. Conditions causing poor circulation (blood flow) or anemia (a reduction in red blood cells) will result in pale gums that may have a touch of pink or be completely white. Because adequate blood flow and oxygenation are so vital, problems with these can cause your cat to feel very unwell and are often life-threatening.

Assessing cat gum color is a quick and simple way to gain important information about your cat’s health. Try checking your cat’s gums anywhere from once a week to once a month.

How Do You Check Your Cat’s Gums?

Having help makes things easier to check your cat’s gums, but doing it on your own is entirely possible.

Choose a time when your cat is relaxed. Most cats love head, chin, and cheek rubs, so start with these to see if your kitty is up for being touched.

I prefer to hold the cat from behind, with my arms gently cradling the sides of their body. I give plenty of praise and pets while gently working my way to their mouth. Finally, I place one hand on top of their head and use the thumb of that hand to raise their upper lip.

A gentle and gradual approach is key to doing pretty much anything with cats. That said, not all cats will tolerate this, so if they put up a fuss, don’t push the issue.

8 Causes of Pale Gums in Cats

When gums appear pale or white, it’s due to a problem with either poor circulation or anemia (sometimes both).

Poor circulation occurs with conditions affecting blood flow. Sometimes only a select part of the body is affected (like frostbite on ear tips), whereas other times the entire circulatory system is compromised (such as with severe blood loss). Gums typically become pale when the entire circulatory system is affected.

Anemia occurs when there is a reduced number of red blood cells in circulation, either due to loss (bleeding), a problem producing new red blood cells, or hemolysis, which is the destruction of red blood cells resulting in hemolytic anemia. Hemolytic anemia usually leads to yellow gums.

Here are some of the most common causes of pale gums in cats:

1. Trauma

Getting hit by a car or attacked by a larger animal are common causes of trauma in cats. Severe bleeding (which can be internal, external, or both) is common with traumatic injuries. When this happens, the body tries to cope by prioritizing blood flow to vital organs. If there is more blood loss than the body can cope with, permanent organ damage or death may occur.

2. Parasites

Some of the most common parasites in cats are voracious bloodsuckers. Hookworms (an intestinal parasite), fleas, and ticks all feed on blood. If the infestation is large enough, blood loss can result in parasitic-induced anemia. Kittens and sick or debilitated cats have the highest risk of developing life-threatening anemia.

3. Infection

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV) are viruses that suppress the immune system and can impair the bone marrow’s ability to create new red blood cells, leading to anemia.

4. Clotting Problem

A complex system of specialized blood proteins and cells (platelets) are responsible for clotting. They’re constantly at work, and without them, even the smallest bruise or cut would bleed uncontrollably.

One of the most notorious causes of clotting problems in cats is accidental poisoning with anticoagulant rodenticide (rat bait). Affected cats may have pale, bleeding gums, nose bleeds, trouble breathing, bloody vomit or urine, and weakness; however, signs vary greatly, depending on where the bleeding is happening in the body.

It’s rare, but some cats are born with a clotting disorder, the most common being Haemophilia A or B. Both conditions result in deficient levels of a clotting factor (specialized blood protein) essential for clotting.

Liver failure and severe blood infections (sepsis) may also result in clotting problems in cats.

5. Cancer

The effects of cancer are vast and varied, depending on the cancer type and area of the body that’s affected. Cats may become anemic from internal tumors that chronically bleed or suddenly rupture. (Internal tumor rupture is much less common in cats than dogs.) More common feline cancers, like lymphoma, can invade the bone marrow, interfering with the production of new red blood cells, while other cancers may trigger hemolytic anemia.

6. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Chronic kidney disease is one of the most common conditions affecting senior cats. Cats with CKD may experience weight loss, lethargy, poor appetite, and the need to drink and pee excessively.

Some cats with CKD are prone to anemia, which can reduce their lifespan and quality of life. Healthy kidneys produce a substance called erythropoietin, which stimulates the bone marrow to produce red blood cells, but this process is impaired in cats with CKD.

Additionally, toxins that are normally eliminated by the kidneys can build up in the bloodstream and cause red blood cell fragility, meaning they don’t last as long in circulation.

7. Heart Disease

The most common type of feline heart disease is called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition causing the walls of the heart muscle to thicken. As the disease advances, the heart cannot pump blood effectively through the body, leading to poor circulation and serious complications such as congestive heart failure or a saddle thrombus (large blood clot).

8. Shock

Shock is a state where the body’s ability to cope with a disease or injury has been overwhelmed. There are a few types of shock, but it generally occurs when there is inadequate delivery of oxygen to the tissues. The risk of permanent organ damage or death is high.

Many different conditions can lead to shock, such as severe dehydration, anaphylaxis (major allergic reaction), sepsis, hypothermia, certain toxins, and traumatic injuries.

What to Do if Your Cat Has Pale Gums

If your cat’s gums are obviously pale or white, this is an emergency. Typically, other signs will be present, such as lethargy, weakness, and rapid breathing. The best thing you can do is keep them warm and get them to the veterinarian right away.

If the cause is due to visible blood loss, apply pressure to the wound with a clean towel until you can get to your veterinarian. If possible, have someone help you tend to your cat and get you to the animal hospital.

What if your cat has pale gums but is acting normal? Some conditions that cause pale gums, such as mild, slowly developing anemia, don’t present as dramatically, and cats may not show many signs that something is amiss. A slight pallor to the gums can be hard for even the most discerning pet parent to notice. Also, gum color may fluctuate slightly without your cat being seriously ill. If you are unsure about your cat’s gum color, contact your veterinarian for advice.

How to treat pale gums in cats depends on the cause, and in most circumstances, the cause won’t be immediately clear. For pale cat gums, a veterinary assessment and diagnostic testing will be necessary in order to receive an accurate diagnosis and treatment plan.

How to Prevent Pale Gums in Cats

Unfortunately, we can’t always prevent our cats from getting sick; however, there are some steps you can take to reduce the risk of conditions that cause pale gums.

Consider staying indoors. Whether to keep your cat inside or let them outdoors is a personal choice, but on average, we know indoor cats live longer, healthier lives than outdoor cats. Outdoor cats are much more likely to have a traumatic injury. They’re also more exposed to parasites and infections, and more at risk of hypothermia in cold climates.

Be aware of toxins. It’s important to learn about common toxins in cats and keep these away from your furry friend.

Don’t forget checkups. Regular veterinary check-ups are a crucial part of keeping your cat healthy and identifying problems early. During a routine examination, your veterinarian can assess your cat’s overall health, identify possible concerns, and provide vaccines and parasite control that protect your cat.

Lungworm in Cats

- 2024-12-09T13:06:09

- Joanna Woodnutt, MRCVS

Lungworm is a generic term for a parasite that infects the lungs. I’ve thankfully never diagnosed a case of cat lungworms during my veterinary career so far. While it can go undetected and not cause symptoms, feline lungworm can be serious in young cats, so it’s worth knowing what to look for — especially if you have an active, outdoor cat who enjoys hunting.

Let’s look closely at lungworm in cats, how they get it, and how to protect your cat.

What Is Lungworm in Cats?

Cats can get several different lungworms in North America. The most common type in domestic cats is Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, but cats can also get several other species of lungworm.

Cats with lungworm have adult worms living inside their lungs, and immature larvae moving around the lungs. The irritation causes coughing, and the worms can take up so much space that cats have problems breathing. It can be distressing for cats, and the symptoms can become severe enough to become fatal — especially in young kittens, who can get the infection from their mother’s milk.

How Do Cats Get Lungworm?

Cats usually catch the lungworm by eating infected rodents or birds (for most species — although one parasite species can also be picked up from cat poop). Once they’ve been eaten, the parasite enters the bloodstream and travels to the lungs, where they mature into adults. These adult parasites produce eggs, which hatch, and the first-stage larvae are coughed up and swallowed.

These tiny larvae survive the stomach and intestines and are then passed in the poop, ready to infect a slug or snail. Inside the slug or snail they mature, and are then able to infect cats again — although usually, they first infect a mouse or bird that eats the slug or snail.

This means outdoor cats, and especially strays who hunt a lot, are much more likely to have cat lungworm than those who spend most of their time indoors.

Most lungworms need to spend some time in an intermediate host (in this case, the snails/slugs) to develop properly. This means cats can’t normally catch lungworm from one another. But one type of lungworm is infectious as soon as it’s passed in feces and can be caught by in-contact cats and other animals, including humans, causing bronchitis with a productive cough.

Signs of Lungworm in Cats

The signs of lungworm in cats vary hugely. In some cases, cats can be infected with lungworms without showing any signs at all. This is called an asymptomatic infection. This is more likely at an early stage of the disease. As the adult worms grow and take up more space and produce more eggs and larvae, there’s more damage to the lungs and more symptoms. Asymptomatic infections are also more likely if cats are infected with only a small number of worms. The more larvae they ingest, the worse their symptoms are likely to be.

A cat with lungworm might have:

- A cough (usually a productive one, followed by a swallow)

- Nasal discharge

- Fever

- Fast breathing

- Lymph node enlargement

- Lethargy

- Weight loss

- Difficulty breathing

- Blue-tinged gums

In some cases, lungworm infections are undiagnosed until animals die under anesthetic, and the infection is found on post-mortem. One important thing to note is that you don’t expect to see worms in cat poop if they’ve got lungworm. Although the lungworm parasite does come out in the poop, it’s the very tiny first-stage larvae and not the adult worms. They can’t be seen without a microscope, so worms in a cat’s poop are not a sign of lungworm (although mixed infection with several types of worms is possible, too).

Diagnosing Lungworm in Cats

Vets usually suspect lungworm based on a cat’s history and age. A young cat who spends lots of time outdoors is more likely to have feline lungworm than an indoor-only cat or one who is much older.

Once the adult worms are old enough to start producing eggs (about 4-6 weeks after the infective larvae were ingested), then vets can usually find first-stage larvae in the poop. A smear of poop is examined under the microscope to look for the first-stage larvae, which are very active and easy to see (although difficult to distinguish from some other larvae). Eggs aren’t produced consistently, so collecting poop over several days or trying again several times might help.

There are several other tests that might help identify lungworm in cats. The best is probably a PCR test, which checks the poop (or a throat swab) for the presence of lungworm DNA. This is low-risk and not very invasive, with a high chance of success. Worms might also be seen on a lung wash or Bronchioalveolar Lavage – BAL, which is where sterile water is pushed into an anesthetized cat and then sucked out, and the liquid is sent for testing. The problem with this technique is that it’s invasive and risky, especially to a cat who already has symptoms of lung trouble.

While lungworm in cats can’t be diagnosed on X-ray alone, it’s likely your vet will take X-rays as part of a workup for coughing in cats as it can help rule out other diseases. Unfortunately, the signs of cat lungworm on X-ray are non-specific. The thickened airways and pneumonia can look like asthma, which causes similar symptoms. Similarly, while they won’t usually see any worms, using a video camera (bronchoscope) can be helpful to rule out other diseases and visually see the damage to the lungs to help guide treatment.

Lungworm in Cats Treatment

Treating the actual feline lungworm itself isn’t particularly difficult. Many anti-parasite products on the market have been proven to cure the lungworm. The main problem comes with treating the inflammation, secondary infections, and any complications caused by the worms themselves. In cats with moderate to severe symptoms, antibiotics and anti-inflammatory steroids may need to be given as well, and they may need to be hospitalized for oxygen therapy while the treatment begins. There are no home remedies to cure lungworms in cats.

Once your cat has had their anti-parasite medication, you’ll need to watch them closely. It’s possible for the death of the parasites to cause cats to feel worse for a short time, so keep an eye on their breathing and energy levels and call your vet if you have any concerns.

Lungworm Medicine for Cats

Many common anti-parasite medications can treat lungworms in cats, although their use against lungworms may be considered “off-label.” The following are most commonly used:

- Imidacloprid + moxidectin (Advantage Multi): a spot-on anti-parasite medication that kills adult worms

- Emodepside + praziquantel (Profender): a spot-on anti-parasite medication that kills adult worms

- Fenbendazole (Panacur): An anti-parasite oral paste that kills the adult worms

- Prednisolone: An anti-inflammatory steroid

Cost of Treating Lungworm in Cats

Unfortunately, because lungworm is fairly rare, investigations to get a diagnosis can be expensive, especially as vets normally rule out more common causes of similar symptoms first. This means the cost of diagnosis can be high, ranging from $200-$1,000. Because lungworm in cats can usually be treated with normal anti-parasitic drugs, the actual cost of the drugs to treat lungworm can be quite low, as little as $50. The more severe the symptoms, the more it costs to treat, with cats needing hospitalization costing $300-$600 to treat.

How to Prevent Lungworm in Cats

Because most feline lungworms are spread through eating small prey, preventing cats from hunting will reduce the chance of them catching lungworm. Some cats find it very stressful to be kept indoors, but anti-hunting collars may help reduce their catch rate even if you’re letting them out.

For those prolific hunters or for stray cats, it’s possible to prevent feline lungworm with monthly medications from your vet. If this is the case, talk to your vet about your cat’s parasite prevention to make sure they’re covered.

Nasal Polyps in Cats

- 2024-12-02T16:40:44

- Emily Swiniarski, DVM

When a cat gets a stuffy nose, it’s easy to assume a kitty cold is the culprit…especially if they’re also sneezing and sniffling. But if your kitty’s stuffy nose persists, it may be time to consider other causes, including nasal polyps in cats.

Feline nasal polyps can cause similar symptoms to the common cat cold. However, nasal polyps in cats don’t go away on their own over time like colds do. And they can cause more complicated health issues.

So how can pet parents tell if their cat has nasal polyps? More importantly, what should they do about it? Here’s everything you need to know about nasal polyps in cats so you (and your kitty) can breathe easier.

What are Nasal Polyps in Cats?

Polyps are what we call abnormal fleshy growths that can develop in many parts of the body, in both humans and animals. These inflammatory masses are generally benign (non-cancerous). They consist of epithelial cells and cells that respond to inflammation, like white blood cells. Unlike tumors, they do not spread to other tissues.

In cats, polyps can occur in the ear (aural polyps) as well as the nose and throat region (feline nasopharyngeal polyps).

Nasal polyps in cats grow from the inner lining of the nasal cavity or sinuses. They can also develop deep within the head, where the nasal cavities begin.

Feline nasal polyps are generally pink or off-white in color. The fleshy growths may appear soft and rounded, attached by a stalk to nasal tissue or the inside of the nasal cavity. They usually occur on one side, not both sides, but this does occur in 13-24 percent of cases (1,2).

Nasal polyps are not very common. They tend to occur most often in young cats around the age of one year. However, polyps can develop in cats as young as three months of age and much older than one year. No single breed is prone to nasal polyps.

Polyps in Cat’s Nose: Causes

The exact cause of nasal polyps is unknown. The inflammatory nature of the growths suggests some sort of immune response, but it remains unproven. Theorized (possible) causes include:

- Upper respiratory diseases, such as feline herpesvirus-1 and feline calicivirus. However, multiple studies have failed to prove this link.

- Feline retroviruses (feline leukemia virus and feline immunodeficiency virus), but multiple studies have failed to prove this.

- Bacterial infection is common when cats have a nasal polyp. However, the polyp doesn’t go away with antibiotics, so bacteria cannot be the only cause.

- Chronic rhinitis is a condition of chronic inflammation in the nasal cavity. However, this is diffuse (occurring throughout the cavity), not a mass growing from a single specific place.

- Genetics may play a role. In some litters of cats, more than one cat is affected.

Symptoms of Nasal Polyps in Cats

Cats with nasal polyps tend to have a very stuffy nose. However, this makes nasal polyps in cats difficult to distinguish from the common kitty cold.

In rare cases, pet parents can actually see a small pink fleshy growth sticking out of their cat’s nose. Though, most of the time, polyps are not obvious to a casual observer.

Some additional cat nasal polyp symptoms to watch out for include:

- Sneezing

- Open-mouth or heavy breathing

- Loud breathing that sounds like snoring

- Difficulty swallowing

- Difficulty breathing

- Discharge from the nose or eyes

These are also signs of upper respiratory disease in cats caused by herpesvirus-1 or feline calicivirus. However, such symptoms tend to improve after about two weeks in cats with these viruses.

Cats with nasal polyps are typically very congested and tend to remain so for over four weeks. Persistent stuffiness and very loud breathing are key indicators that nasal polyps may be the cause.

Diagnosing Nasal Polyps in Cats

The majority of polyps cannot be diagnosed with a veterinary exam. In rare cases, the growths may be visible externally. But your vet will still conduct a thorough exam to check your cat’s airways and rule out other problems, like upper respiratory disease.

To find nasal polyps, your veterinarian will need to anesthetize your kitty so he’s sleeping. While looking deep into the mouth, your vet will pull the soft part of the roof of the mouth forward to see more of the nasal cavity. If a mass is present, a nasal polyp is likely.

The only way to know for sure if a growth is a polyp is to examine the tissue under a microscope. A cat nasal tumor or growth could indicate nasal cancer in cats. So it is best to remove the growth and test it, especially nasal polyps in older cats.

Treatment for Feline Nasal Polyps

Many pet parents ask, “Are nasal polyps in cats dangerous?” To answer that, it’s important to know that cats breathe primarily through their noses. Since nasal polyps won’t go away on their own, treatment is essential to eliminate the danger and ensure cats can breathe easily.

There are three main treatments veterinarians use to combat nasal polyps:

1. Cat Nasal Polyp Surgery

Removal by traction is a minor surgery veterinarians use to remove simple nasal polyps in cats.

Usually, the vet will make a small incision in the soft part of the roof of your cat’s mouth. Then they’ll use a surgical instrument to very slowly and carefully pull on the polyp with gentle traction. Ideally, the polyp will tear off with the stalk at the point of origin.

In some cases, more advanced surgery may be necessary to remove a polyp. For example, if a polyp develops deep inside the head, removing it by traction may be impossible. If a nasal polyp reoccurs after minor surgery to remove it, more advanced surgical treatment is in order.

Cat nasal polyp surgery cost can vary, depending on the complexity. Using traction for removal is a quick procedure that usually costs a few hundred dollars. Advanced surgery can involve a special camera and instrument called rhinoscopy. This would typically cost thousands of dollars and require a specialist.

2. Steroids

Your vet may prescribe prednisolone (or prednisone) after surgery to reduce inflammation in the nasal cavity. You may have to administer the medication for several weeks to reduce the chance of the polyp forming again.

Nasal polyps can recur in cats, particularly if the stalk of the polyp remains after a vet removes the growth. However, several weeks of steroid treatment post-surgery can help reduce the risk of recurrence. According to one study of cats who did not receive steroid treatment after surgery to remove nasal polyps, regrowth occurred between 15-50 percent of the time. (3)

3. Antibiotics

Often, nasal polyps go hand in hand with secondary bacterial infections in cats. While antibiotics do not directly treat the nasal polyp, vets often prescribe them to treat infection, reduce inflammation, and help your kitty breathe comfortably.

How to Help Cats with Feline Nasal Polyps at Home

In addition to veterinary treatment for nasal polyps, there are some things pet parents can do at home to help ease a cat’s recovery

Provide steam showers if your kitty is very congested. Run hot water in the shower and place your kitty in the bathroom while the bathroom fills with steam. Breathing the humid air for around 30 minutes can help reduce congestion so they can breathe easier.

Another way to do this is to use a nebulizer filled with sterile saline solution. Place the nebulizer in or in front of a carrier that’s holding your cat. Cover the carrier with a towel to trap the mist inside, but leave some holes open to encourage airflow. After about 15-30 minutes, the aerosolized mist from the nebulizer should help clear your cat’s airways.

How to Prevent Cat Nasal Polyps

In general, there is no way to prevent nasal polyps in cats as the cause is unknown. However, if your cat develops symptoms of an upper respiratory infection and they worsen or linger, seek treatment from your veterinarian to avoid prolonged inflammation.

References

- Kapatkin, Amy S et al. “Results of surgery and long-term follow-up in 31 cats with nasopharyngeal polyps.” Journal of The American Animal Hospital Association 26 (1990): 387-392.

- Hoppers, Sarrah E et al. “Feline bilateral inflammatory aural polyps: a descriptive retrospective study.” Veterinary dermatology vol. 31,5 (2020): 385-e102. doi:10.1111/vde.12877

- Anderson, D M et al. “Management of inflammatory polyps in 37 cats.” The Veterinary record vol. 147,24 (2000): 684-7.

Cat Wheezing: What It Sounds Like and Why It Happens

- 2024-11-25T17:37:45

- Alicia Ashley, DVM

When it comes to kitty noises, meows and purrs are what we expect to hear from our feline friends. And as astute pet parents, we usually have a good idea of what these sounds mean: feed me, pet me, please let me in. But would you recognize the sound of a cat wheezing? If the answer is no, don’t worry, you’re not alone.

Wheezing is challenging to decipher and often gets confused with other types of noisy and labored breathing in cats. Snoring, gagging, coughing, sneezing, sniffling, regurgitating hairballs (more on this later), and wheezing — there’s a lot to keep straight. And when it comes to your cat’s breathing, there’s a lot at stake. If you notice your cat making weird breathing noises, it’s important to contact your veterinarian.

Here, we’ll explain the ins and outs of wheezing, including what causes it, what it sounds like, and common treatments.

Why Is My Cat Wheezing?

A cat’s respiratory tract includes their nasal passages, pharynx (throat), larynx (voice box), and trachea (windpipe) that branch into smaller airways called bronchi and bronchioles before terminating into sac-like clusters called alveoli (where oxygen and carbon dioxide are exchanged).

In a healthy respiratory tract, air flows unobstructed through the airways, and while not completely silent, the process is normally quiet. If the airways become partially obstructed or narrowed, this changes how the air flows and can lead to noisy, high-pitched breathing called wheezing.

If your cat is wheezing, this is abnormal, and depending on the cause and presence of other signs, can indicate an emergency.

What Does Cat Wheezing Sound Like?

Cat wheezing is a high-pitched, sometimes whistle-like sound that happens while breathing. The high-pitched sound is key to differentiating it from other types of noisy breathing.

A cat wheezing sound can be so quiet it’s only audible with a stethoscope or so loud it’s heard by anyone within earshot. Wheezing can occur continuously or as intermittent episodes and may happen during inhalation, exhalation, or with a cough.

Wheezing during exhalation or coughing is typical in cats with lower airway conditions causing bronchitis, such as asthma or lungworm. Bronchitis is a general term used to describe inflammation from any cause in the lower airways.

Wheezing that originates from narrowed upper airways (the upper trachea or voice box) is called stridor. It still has a high-pitched quality (but may sound harsher) and occurs during either inspiration, expiration, or both. Stridor is associated with several upper airway conditions including infections, foreign bodies, and tumors.

On the other hand, cats with stertor typically have an obstruction or narrowing in the highest part of the respiratory tract (within the nose or throat). Stertor is a lower-pitched, loud snoring sound and is not considered wheezing. Stertor has many potential causes, including a stuffy or inflamed nose, nasopharyngeal polyps, or nasal foreign bodies or tumors, or may be due to the condensed anatomy of brachycephalic (flat-faced) cat breeds such as Persians.

Stertor doesn’t always mean something is wrong. It’s normal for some cats to snore while sleeping or resting in a certain position. If you’re unsure if your cat is snoring or wheezing, check with your veterinarian.

5 Causes of Wheezing in Cats

Feline Asthma/Chronic Bronchitis

Several terms are used interchangeably for feline asthma, so you may also see it called feline allergic bronchitis, feline bronchial asthma, or chronic bronchitis.

Some veterinarians refer to chronic bronchitis as a closely related but separate entity from feline asthma, while others lump them together as the same condition. They likely have different underlying causes but can be impossible to tell apart and are generally treated the same. If you feel confused by the terminology, you’re not alone. It’s an area requiring more research. For this article, we’ll use the term feline asthma.

Feline asthma is a lifelong condition and one of the most classic causes of wheezing in cats. Asthmatic cats have an exaggerated allergic response to environmental allergens such as dust, smoke, pollen, scented products (candles, essential oils, fabric sprays), and strong cleaners (bleach).

In response, their lower airways spasm and become irritated, narrowed, and plugged with mucus. Affected cats may cough, wheeze, and have labored breathing and shortness of breath, especially after exertion. A characteristic wheezing sound happens when air is forced through the narrowed airways.

Signs of asthma tend to come and go but worsen without treatment and can lead to asthma attacks.

Here are the signs of an asthma attack:

- Your cat stops what they’re doing and crouches low to the ground, with a flat back and their head and neck extended.

- They have several forceful, harsh exhales (coughs) that may produce a high-pitched wheezing sound, with their mouth typically closed.

- They may swallow several times but not expel anything from their mouth (an exception may be if they cough enough to trigger the gag reflex and subsequently vomit).

- Cats may carry on as usual after an episode like this; however, those who don’t recover quickly or develop other signs of difficulty breathing need emergency veterinary care.

An episode like this is often confused with “coughing up a hairball,” but hairballs don’t cause cats to cough and wheeze. Hairballs come from the digestive tract and are vomited up. Cats will forcefully gag (open their mouth wide and stick out their tongue) and have strong abdominal contractions, like a rhythmic wave, before ultimately vomiting up a hairball. They usually don’t crouch down like they do when coughing and wheezing.

If you’re unsure if your cat is wheezing or bringing up a hairball, it’s extremely helpful to take a video to show your veterinarian.

Parasitic Bronchitis

Several species of parasites, known as feline lungworms, can set up shop in a cat’s lungs and cause parasitic bronchitis (inflammation in the lower airways caused by parasites), which can lead to wheezing. One of the most common lungworms, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, is carried by snails and slugs. Typically, cats become infected by eating an animal (mouse, bird, lizard, frog) that ate an infected snail or slug.

Outdoor cats have the highest risk of lungworm. Once a cat ingests the parasite, it makes its way to the lungs, where adult female lungworms lay their eggs. From here, the eggs hatch into larvae, travel up the airways, are coughed up, swallowed into the digestive system, and finally, passed in the cat’s feces.

If only a small number of worms are present, a cat may have very mild or no symptoms at all, but high numbers of worms can wreak havoc on a cat’s airways and lead to life-threatening complications.

Signs of lungworm include:

- Wheezing

- Coughing

- Labored breathing

- Sneezing

- Lethargy

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Fever

Respiratory Infections

Any viral, bacterial, or fungal respiratory infection can potentially cause wheezing in cats.

Common viral upper respiratory infections, such as calicivirus and feline herpes, are notorious for causing cat wheezing and sneezing, especially among kittens and in shelter environments.

Affected cats may have stertor (that loud, snoring-like sound) from a stuffy nose, while an inflamed voice box or upper trachea may result in your cat wheezing and coughing.

Common signs include:

- Sneezing

- A runny and congested nose

- Eye discharge

- Coughing

- Wheezing

- Fever

- Lethargy

Bacterial upper respiratory infections, such as Mycoplasma felis and Bordetella bronchiseptica, may occur secondary to a viral infection. Typically, they cause similar but potentially more severe symptoms and can progress to pneumonia.

Compared to viral and bacterial respiratory infections, fungal respiratory infections are relatively rare in cats (although more common in some geographical areas) and tend to affect either the nasal passages or deeper lung tissues.

Upper Airway Tumors

Some upper airway tumors cause wheezing in cats. This may happen if a tumor growing outside of the airway (such as in the front of the neck) puts pressure on the voice box, or if tumors inside the airway, such as laryngeal inflammatory polyps or lymphoma, obstruct it from within.

In these circumstances, wheezing typically occurs more predictably, such as every time a cat breathes or is in a certain position, and it tends to worsen over time. Other signs may or may not be present.

A Foreign Body

Occasionally, your cat may chow down on something that travels the wrong way and lodges itself in the respiratory tract. With complete upper airway obstructions, air can’t move around the obstruction, and no breathing noises can be heard. This is obviously a dire situation that is quickly fatal. Fortunately, this is rare in cats.

However, partial airway obstructions happen on occasion. I recall a cat who was rushed in to see me as an emergency — she was wheezing loudly and gagging as if desperately trying to rid something from her throat. This all happened shortly after getting a delicious salmon treat. Can you guess what was stuck in her airway? Amazingly, she coughed out the offending fishbone and had a full recovery. Nine lives indeed!

How to Treat a Wheezing Cat

When it comes to how to help a wheezing cat, a consultation with your veterinarian is an essential first step. Wheezing is a sign of an underlying respiratory issue stemming from several different causes, so treatment and prognosis vary considerably. Once your veterinarian makes a diagnosis, they will start a treatment plan that may include medications, procedures, and addressing factors in the home environment.

Feline asthma is a chronic condition managed with medications, including oral and inhaled (using an asthma inhaler) anti-inflammatories (steroids) and bronchodilators. At home, triggers such as smoke, dust, and strong cleaning and scented products must be avoided, and some veterinarians advocate using air purifiers with a HEPA filter.

Most respiratory infections are treated with medication that fights the specific type of infection.

In cats, a typical viral upper respiratory infection generally doesn’t require treatment beyond supportive care (keeping their face and eyes clear of discharge, using a humidifier, warming up food to encourage appetite, etc.) — kind of like when we have the common cold. Occasionally, in more severe or challenging cases, veterinarians prescribe antiviral medications.

If your veterinarian suspects a bacterial or fungal infection, they will treat using antibiotics or antifungal medications.

Fortunately, lungworm is treatable with antiparasitic medication, such as fenbendazole. Mildly affected cats usually don’t need any other treatment, whereas more severely affected cats may require anti-inflammatories and additional supportive care.

Some tumors affecting the airway can be treated with surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, or a combination of the three. The treatment will depend on the tumor type and location, the extent of its growth, and the general health of your cat.

Foreign bodies in the nose can sometimes be flushed out with saline or removed with a small grabbing tool. If visible, a foreign body in the throat may also be retrieved with a grabbing tool.

However, foreign bodies in the windpipe or deeper airways require removal with a bronchoscopy procedure. This is where a tiny camera and special instruments are passed into the airway to retrieve the object. If this fails, surgery to remove the affected part of the lung may be performed.

Medicine for Cat Wheezing

- Glucocorticoids (steroids) to decrease airway inflammation

- Bronchodilators to reduce airway spasms

- Antibiotics for bacterial infections

- Antivirals for viral infections

- Antiparasitics for parasitic infections

- Antifungals for fungal infections

- Chemotherapy drugs for some types of cancers

When to Worry About Wheezing in Cats

If wheezing is accompanied by other signs of respiratory distress (i.e., your cat struggling to breathe) see a veterinarian immediately. These signs include:

- Open-mouth breathing

- Rapid breathing (>40 breaths per minute at rest)

- Labored breathing (shallow and/or exaggerated abdominal and chest movements)

- Pale or blue gums

- Changes in normal behaviors (not eating or drinking, lethargic)

If your cat is wheezing but otherwise seems okay (they have no other signs of distress, are exhibiting normal behaviors, eating and drinking, etc.) they may not need immediate emergency treatment. They should, however, be seen by a veterinarian soon.

10 Symptoms of Blocked Bile Duct in Cats

- 2024-11-20T03:37:35

- Sarah J. Wooten, DVM

A blocked bile duct can make a cat very ill and result in big veterinary bills. But what exactly is a blocked bile duct and how can pet parents spot this condition?

Read on to learn more about bile duct obstruction in cats, including signs to watch for and next steps to take.

What Is a Blocked Bile Duct?

Before we get into bile duct obstruction in cats, it is helpful to understand a bit about cat bile duct anatomy. One of the functions of the mammalian liver is to make bile, a yellow-green liquid that aids the intestines in digesting food. Small bile ducts collect bile from the lobes of the liver and transport bile via the common bile duct to the intestines where it is used to digest food. Extra bile is stored in the gallbladder, which is linked to the bile ducts inside the liver. Disease anywhere along the bile ducts or nearby organs can result in bile duct obstruction and the accompanying symptoms.

Bile duct disease is also called cholestasis. Bile duct obstruction in cats often occurs when there is inflammation in the liver, gallbladder, or bile ducts. In those cases, the disease is called cholangitis or cholangiohepatitis.

Because the bile ducts are sensitive to what is going on around them in the nearby organs, bile duct obstruction due to inflammation in the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, or small intestines is moderately common in cats.

Bile duct obstruction can happen in any age cat, but is more common in middle aged cats. Cats with a history of liver inflammation, intestinal parasites, or cats who are predisposed to inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), gallstones, or repeated bouts of small intestinal or stomach inflammation are at increased risk for bile duct obstruction.

10 Symptoms of Blocked Bile Duct in Cats

Bile ducts are closely associated with the liver and gastrointestinal system, and the symptoms of a blocked bile duct reflect this relationship. Symptoms of blocked bile duct in cats are notoriously non-specific and can occur all of a sudden or wax and wane over a period of weeks or months.

Symptoms of blocked bile duct in cats are vague, but include:

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Increased hiding or lethargy, other behavioral changes

- Changes in appetite, either up or down

- Weight loss

- Abdominal pain

- Jaundice (yellowed skin, eyes, and gums due to a buildup of bile)

- Bleeding tendencies, increased bruising, bleeding gums

- Swollen abdomen

- Pale stools or orange urine

What Causes Bile Duct Obstruction in Cats?

There are a few reasons why bile ducts can become obstructed. The most common reason is inflammation in a neighboring organ, such as the liver, gallbladder, intestines, or pancreas, externally compresses the common bile duct, causing obstruction. Additional causes include:

- Gallstones

- Intestinal parasites

- Cancer

- Anatomical malformations (usually seen in young cats)

- Duct fibrosis and stricture secondary to trauma or peritonitis

Diagnosis

Because the symptoms of bile duct obstruction in cats are so vague, it can be tricky for a veterinarian to diagnose. A veterinarian will obtain a history by asking you questions and then conduct a physical examination. Based on the history and physical exam findings, a veterinarian will then recommend laboratory testing and imaging studies. These can include:

- Complete blood count (to check red blood cells and platelets, may see a low blood count)

- Serum chemistry (to check electrolytes and internal organ function, often see elevated liver enzymes, increased bilirubin, additional abnormalities include changes in glucose, albumin, cholesterol, and globulins)

- Urinalysis (often see bilirubin crystals)

- Serum bile acids (typically increased, indicates bile dysfunction)

- Coagulation tests (to determine the cause of bleeding)

- Fecal examination (to look for parasites)

- Abdominal radiographs (X-rays, may be able to see gallstones)

- Abdominal ultrasound (more sensitive test, may see distended bile ducts or gallbladder, pancreatitis, etc.)

Depending on what your veterinarian sees in the initial tests, they may recommend additional tests, such as a liver biopsy.

Treatment

Treatment for a blocked bile duct does vary depending on the underlying disease condition and how sick the cat is, but in general, bile duct obstruction requires hospitalization and inpatient care. These cats feel awful, are usually painful and nauseous, and early intervention is key to prevent secondary problems like hepatic lipidosis from occurring.

Mainstays of treatment for most cats with bile duct obstruction include:

- Intravenous fluid therapy to rehydrate and balance electrolytes and vitamins (veterinarians often add water soluble vitamin B to IV fluids)

- Vitamin K

- Vitamin E (antioxidant)

- Antibiotics for bile duct infections and before surgery

- Appropriate nutrition (fat restricted)

- Ursodeoxycholic acid AFTER the bile duct has been decompressed (dissolves gallstones and thins out bile fluid)

- Gastro-protectant medications, such as antacids (famotidine), sucralfate, or omeprazole

- Pain medication as appropriate

In addition to these treatments, a cat with an obstructed bile duct needs the bile duct unobstructed. Treatment for this varies depending on what is causing the obstruction, but can range from surgical correction to hospitalization for pancreatitis.

A cat with a blocked bile duct often will stop eating, which must be addressed if it happens. Ways to address inappetence in a sick cat include appetite stimulants or feeding a liquid diet through a stomach tube.

Cost

Cost of treatment for bile duct obstruction is high, and includes initial testing, hospitalization, and surgery if required:

- Initial testing costs can range from $300-$1,000

- Hospitalization can run several hundred dollars per day

- Surgery will cost $1,000-$3,000

- Take-home medications will likely cost $100 or more

After your cat has been discharged from the hospital, your veterinarian will want you to bring the cat back for recheck examinations and testing to make sure the condition has resolved. This includes checking the bile duct as well as checking coagulation and other laboratory tests. Your veterinarian may also want to ultrasound your cat’s belly again to ensure everything is healing.

Recovery & Management

If the cat has an obstruction due to pancreatitis that is fully resolved, the prognosis is good. The prognosis for other cats with bile duct disease depends on several factors:

- The cause of obstruction and whether it can be resolved

- The health of the bile duct (secondary scarring and strictures make the prognosis worse)

- The overall health of the cat

- The motivation of the pet parents to care for the cat

If your cat has recovered from a bile duct obstruction, then it is possible for your cat to still live a long and happy life, however, there will be some things that your veterinarian will want you to do to ensure that the cat doesn’t relapse. These can include:

- Regular rechecks that may include laboratory tests or imaging studies